Maps for today’s video:

Transcript

Hello, Europeanists! This is our video for Week 13, Day 1. Our topic is upheaval in Eastern Europe, and our teaching assistant is Dante.

It was great to meet with all of you last week and talk about your final papers. I hope your work continues to go well. This is a friendly reminder that your final drafts are due on Friday, May 8 at 10pm, and you should submit them on Sakai. If you have any questions between now and then, or if you want to meet with me again, or if you want to send me a rough draft for comments, I’m happy to help with those things. Just let me know by email.

Looking ahead from here, our last day of class is fast approaching. For our final class meeting, I would like us to get together one last time as a group on Teams. We’ll meet at our regular class time (9:00am EST) on Tuesday, May 5. You should get an email about that from Teams, so please look out for that. If anyone is in a time zone that would make that a really early time to meet, please let me know. I don’t imagine we’re going to talk for the whole time, so we could start a bit later. Also, if anyone unable to join a class video meeting, please email to let me know about that. I’ll make sure you have an alternative option.

Today we’re discussing primary sources that address two key moments in late 20th c European history. Timothy Garton Ash’s The Magic Lantern concerns the collapse of the Eastern Bloc in Warsaw and Berlin. I gave you the context for that in my previous video, so I won’t repeat it here. Feel free to review our video from Week 12 if you could use a refresher. Timothy Garton Ash is a British journalist. He spent the 1980s reporting on Eastern Europe and, as you read, he was an eyewitness to the collapse of the Eastern Bloc in 1989. He wrote this book in 1990, so it gives us his impressions of those events when they were still fresh.

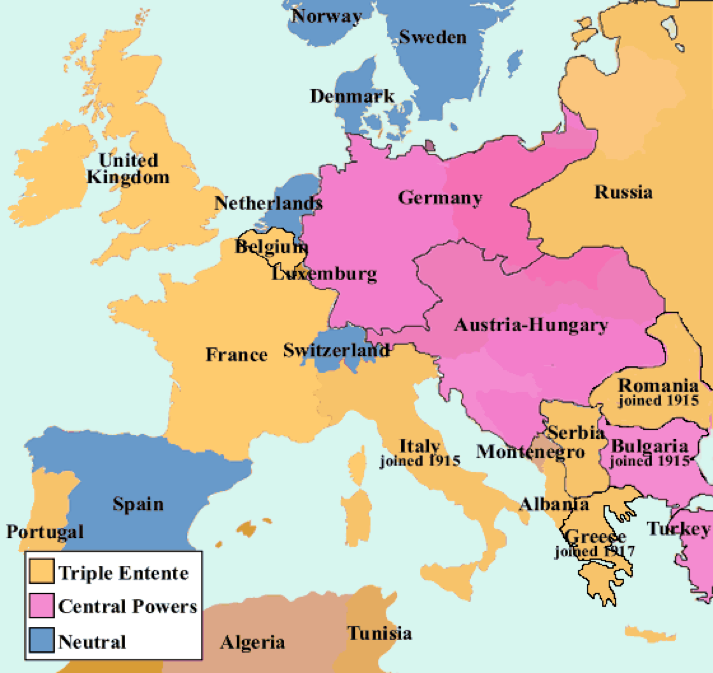

Slavenka Drakulić’s Café Europa dates from a bit later, the mid-1990s in the former Yugoslavia. Yugoslavia was a complicated country, and for many of you it’s probably not very familiar. I’m going to give you some contextual history, and I’ll include a couple of maps in the transcript to help you get your bearings. You may remember that Yugoslavia was formed out of a collection of territories after WWI. These territories shared a broad sense of ethnic identity—the name “Yugoslavia” means “South Slavs”—and they had a common history of being subject to the Ottoman Empire for much of the modern period. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Serbia and Montenegro became independent; Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia-Herzegovina were taken from the Ottomans by the Austro-Hungarian Empire; and Macedonia remained Ottoman land. After the war, with the two big empires gone, these provinces joined together. They did so more for a sense of security than because they felt a strong affinity for one another. On their own, they were small, and smallness meant vulnerability amidst the uncertainties of the interwar period.

The borders of Yugoslavia remained stable from 1918 until 1990. After WWII, Yugoslavia became a communist country, led by Josip Broz Tito, a war hero who had led the anti-Nazi partisan movement. In 1948, Tito broke with Stalin, and Yugoslavia spent the Cold War as a non-aligned country. During this time, the various populations within the country maintained their separate ethnic and religious identities but continued to live together peacefully, as they had done for centuries. The reason I bring this up is that when war broke out in this region in the early 1990s, much of the coverage in the Western press claimed the war was the result of “age old ethnic hatred” among people who could not overcome their “tribalism.” This framing of the breakup of Yugoslavia is both incorrect and harmful. As Mark Mazower pointed out in his chapters on the interwar period, this is the type of rhetoric Western Europeans use to Orientalize Eastern Europeans—to position them as different, backwards, and uncivilized. In fact, as I hope we’ve learned this semester, ethnic conflicts like the ones that erupted in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s are very much a product of 20th century Europe: its territorial nationalism, its concern with “healthy” and “sick” bodies, and its invention of genocide and ethnic cleansing.

The six republics that made up Yugoslavia began to think about separating in the early 1990s, as they witnessed Soviet republics like Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia break away from the Soviet Union. In 1992, Bosnia-Herzegovina declared its independence. Bosnia-Herzegovina was a diverse republic, containing Muslim Bosnians, Catholic Croats, and Orthodox Christian Serbs, who, again, had lived together peacefully for a long time. That doesn’t mean there weren’t tensions between them, but it wasn’t enough to start a war. However, Slobodan Milosević, the president of Serbia, resented this loss of territory and declared that he would “save” Yugoslavia by bringing Bosnia-Herzegovina back into the fold. He sent in the Serbian army, which was joined by ultra-nationalist Bosnian Serbs. Together they committed genocide against Bosnian Muslims, rounding them up into concentration camps and murdering them.

In 1993, the UN sent peacekeepers into Bosnia, but the safe zone they set up was overrun by Serbian forces. The next year, a US-NATO coalition intervened more forcefully with a massive bombing campaign in Serbia. This campaign was effective; it drove Milosević to the negotiating table and ended the war. But if you talk to Bosnians who lived through these events, as glad as they are to be rid of Milosević and his hateful rhetoric and unjust war, they are not grateful to NATO. To them, the bombing campaign felt like another imperialist invasion, in which a foreign power came in, imposed its will by force, and left without cleaning up its mess. The war formally ended with the signing of the Dayton Accords in 1995, which created two states: a rump Yugoslavia consisting of only Serbia and Montenegro, and an independent Bosnia.

Shortly after the Dayton Accords, the Serbian province of Kosovo, which has a majority Albanian population, declared its independence. Milosević sent in his army, but NATO launched another bombing campaign, which resulted in the Serbian Army withdrawing and, eventually, Kosovo declaring its full independence in 2008. After this adventure, Milosević was well and truly disgraced. In 2001, he was ousted, and the new Serbian government turned him over ot the International Criminal Court to be tried for crimes against humanity. He died in prison in 2006, before his trial was complete.

In the aftermath, former Yugoslavs, who were now citizens of seven different countries, had to figure out how to move on and make sense of the legacy of both the communist period and the Yugoslav Wars. This is the subject of Slavenka Drakulić’s essays in Café Europa.

Leah’s Discussion Questions

1. In Timothy Garton Ash’s chapter “Warsaw,” he describes the elections held in Poland on June 4, 1989, the first in which non-communist candidates were allowed to run for office. He explains that both the Communist Party and Solidarity, the independent workers’ party, were completely surprised that Solidarity candidates won a majority. Three unbelievable things happened: the communists lost, Solidarity won, and the communist acknowledged the election results. Can you unpack Ash’s explanation of why these things were so surprising? What does it reveal about both parties’ relationship to the electorate that neither side expected Solidarity to win? Why do you think the Communist Party respected the election’s results? In your analysis, was the actress right or wrong when she said that communism in Poland ended that day?

2. After the election, Ash writes, “As Solidarity leaders began to engage in real politics… there was more than a touch of nostalgia for the simple truths and moral clarities of the marital law period.” (Ash, 32). What do you make of this idea that it’s harder to be in power than to be in opposition? What new issues and difficulties did Solidarity face? What do you make of Lech Wałęsa, the Solidarity leader who pushed for democracy but had a touch of the dictator in his personality? Is a figure like that necessary to make a revolution happen?

3. As Ash relates, being in power forced Solidarity to accept a number of compromises. Chief among these was the presidency of General Jaruzelski, who had been a staunch foe of Solidarity activists in the 1980s, and the adoption of economic austerity measures. Based on Ash’s descriptions, do you think Solidarity made the right choices in these cases? Why or why not? What else could they have done? Did their compromises help to ensure a peaceful transition to capitalism and liberal democracy in Poland, or were they a sell out?

4. Ash’s chapter “Berlin: Wall’s End” takes us back to familiar territory. Like Serge Schmemann, Ash recounts the rise of the weekly protest movement in Leipzig and the East German government’s decision not to use force against them. Unlike Schmemann, though, Ash gives credit first and foremost to the citizens themselves. He writes, “the people acted and the Party reacted” (Ash, 69) and says that the conductor Kurt Masur played a more crucial role than Party security chief Egon Krenz. Can you unpack this situation? Why does it matter that the protesters “led” in this situation? How does that shape our understanding of these events as historians? What role did other factors play in the Party’s decision-making, like Gorbachev’s recent visit and the Chinese Communist Party’s decision to fire on protesters in Tiananmen Square?

5. According to Ash, many East Germans immediately began thinking about reunification. But this was not such an easy issue. What complications did it raise? Why were East German opposition activists loathe to consider this option? Ash calls these activists “emotional,” but could there be something substantive behind their desire not to “sell out” the GDR?

6. Despite the speed with which the two Germanies reunited, they have in some ways retained an echo of their separation. Even now, if you walk through Berlin, it’s easy to tell when you cross into the East, even where the Wall’s former path is not marked. The Eastern districts are poorer and have shoddier infrastructure. Yet, they’ve also become the home to Berlin’s hipsters and rave community. What do you make of the persistence of difference in Belin 30 years after reunification? Do you think the two halves of the city will always feel different, or is it only a matter of time until this history is erased from the physical landscape?

7. Let’s turn to Café Europa. In her essay “My Father’s Guilt,” Drakulić recounts the story of her father’s life. He fought with the partisans during the war and was a true believer in the Communist Party. Why does she consider him “guilty”? In her eyes, what is he guilty of? Do you agree with this characterization? How does Drakulić’s father compare to Rudolf, the husband of Heda Margolius Kovaly, author of Under a Cruel Star? Are they both guilty? Are they both innocent? Or is it more complicated than that? How do these questions help us think about the difficulties of living through a major change in government?

8. Despite her opposition to communism, Drakulić is angry when she discovers that her mother has started covering up the communist star on her father’s grave. She writes, “I could see that someone was stealing the past from my father, from me, from all of us, and we were just letting it happen—more than that, we even eagerly co-operated in this robbery, in order to cover the traces of the recent past in our own lives.” (Drakulić, 147-148) Can you unpack her feelings here? Why is this past important to her to remember, even though she’s not a communist? Why does she feel strongly about acknowledging the good and the bad things accomplished under Tito? What possibilities arise when parts of the past are erased, including Yugoslavia’s history of fascism between the world wars? Does she convince you that every country must confront its past, or is it sometimes better to leave that past behind?

9. In her final paragraphs, Drakulić applies the lens of guilt to herself and her own generation. Make a close reading of pp. 157-159. Why does Drakulić consider herself guilty? What is she guilty of? Is she right, or is she being too hard on herself? We also live in a country with a troubled history. Are we sometimes guilty of tacitly accepting sugarcoated versions of the past? How can we acknowledge our history while still moving forward?

10. In “People from Three Borders,” Drakulić describes the situation of the people of Istria, a peninsula that has been divided between Croatia, Slovenia, and Italy since the collapse of Yugoslavia. What does nationality mean in Istria? How can we make sense of the Istrians’ claim to be Croatian, Slovenian, and Italian all at once? What do these terms mean to them? How does this situation shape your understanding of the issues of nation and nationalism at the end of the 20th century? How have this century’s events influenced the Istrians’ choices when the answer the question “What are you?”?

11. Drakulić relates that recently, residents of the peninsula have started to claim “Istrian” as their identity, as a form of resistance against nationalist pressures. This may remind us of the situation in this same region (and others) after WWI, as Europeans tried to remake Eastern Europe on the principle of the nation-state. In your analysis, is a return to regionalism the right answer for places like Istria? Is it the right answer for everyone? Or should we look ahead to new solutions rather than back to old ones?

12. At the end of this essay, Drakulić goes shopping with a friend who has three passports. But he dreams of not needing any passports, when Croatia joins the EU. In fact, Croatia did join the EU in 2013. But the EU itself is now being strained by nationalist pressures, both in Eastern Europe, and, of course, in Britain, which left the European Union in January. Can you assess Drakulić’s friend’s dream of a borderless Europe in light of these tensions? Is it a pipe dream? Will nationalism continue to assert itself in the European space in the 21st century? Or are we witnessing nationalism in its final throes of dying away?

I’m answering question 12. I think right now a borderless Europe is just a dream unfortunately. I think that especially because of what’s happening in with Great Britain, it’s hard to see Europe completely becoming one and joining together. I don’t think it’s totally never going to be a possibility. I think one day with time and change and acceptance it totally could become a reality, but at the moment and in the near future because of the refugee crisis and things like nationalism especially it doesn’t look like it’s coming soon.

6.

I think the two halves of the city will feel different as of now, but later on in the future I’d like to hope that the differences would completely disappear. As for the physical landscape, it would seem that parts of the Wall will forever be up to have a historic landmark that explains part of Germans history. Whether the east side stays as the poorer or not, I think that in time it will not be noticeably poorer than the West side. Seeing as hipsters and raves are now inhabiting the area, I think that the area will begin to prosper and increase in revenue.

I am responding to question #5

Immediately considering reunification was a pipe dream in reality. The two sides of Germany had been split for so long with spreads governments they began to develop their own identities. Trying to immediately reunify would’ve been almost like trying to unify two foreign countries. At that point they had completely different economies, identities and governments. They had no plan in place to return to a similar currency or to accommodate one or the others economical strengths and weaknesses. Obviously neither side wanted to “sell out” to the other side after being separated for so long so while emotions did play some roll in their thinking they had more substance behind their reasoning than they were given credit for.

#5

There were numerous complications in reunification. What political structures would look like, how the economic would work–adopt West Germany’s, create a new one–how to deal with stationed Soviet troops. There were also issues lying in an emotional attachment to the GDR. As Ash writes, many East Germans chose to stay in East Germany and had a legitimate belief in socialism and egalitarianism. These same people had clear issues with western ideals even if they found Communism as practiced by the USSR unacceptable. It is too simple to paint the west as a fairy tale hero to the damsel in distress of East Germany. The East Germans had their own beliefs and were not content under Soviet occupation, nor were many willing to submit to western democracy.

12. Drakulic’s friend’s dream of a borderless Europe, is something I find rather debatable. I would not necessarily consider it a “pipe dream” but as of now, and the time this essay was written, is quite unrealistic. Nationalism is a major factor currently because there is a large amount of unpredictability. And instead of uniting as a continent, countries are more drawn to protect their own and their own too. Which raises problematic behavior, we can see from other discussions from this semester. Europe appears to be very spilt on the idea of nationalism, which to my interpretation means it is somewhat dying. Nationalism is a source of security and when there is instability, like there has been in last several years, it gives the sense of protection by uniting with each other. When in reality, there could be better protection if Europe was more completely united. Drakulic’s friend’s dream seems to be something that is an underlying wish of most European citizens but something that is difficult to achieve due to many contributing factors. As of the future of the European Union currently, I believe could be spilt either way. Some countries might want to rely more heavily on one another while others will want to do the exact opposite and become more shut off due to the circumstances of being in the middle of a pandemic. However, the idea of borderless Europe might be far-fetched and never fully, 100% achieved.

I am going to discuss question 12 because this is something we have been seeing in the news in the last few years, especially with Brexit. I think that the picture of unity the EU likes to project only goes so far. All these nations like to act like they are one big family with the same interests, but they all have taken actions throughout the history of the EU that challenge that unity. A borderless Europe, in my opinion, is a dream. For these nations, erasing their physical borders also erases or blurs the borders between their unique cultures.